Is the death penalty constitutional?

Does the death penalty constitute cruel and unusual punishment?

Are innocent people put to death?

Is the death penalty racist?

Is the death penalty cost effective?

Is the death penalty a good use of court resources?

Does the death penalty undermine US global leadership?

US Federal Government Reinstates Death Penalty

Trump

Barr directs the federal government to reinstate the death penalty (July 25). The federal government has ordered the death penalty to be reinstated for the first time in nearly two decades, as Attorney General William Barr directed the Bureau of Prisons to schedule the execution of five inmates after adopting an updated execution protocol. After 16 years without an execution, Barr has directed the head of the Bureau of Prisons to execute “five death-row inmates convicted of murdering, and in some cases torturing and raping, the most vulnerable in our society — children and the elderly” in December and January, according to a statement from the Department of Justice.

The Trump administration is bringing back federal executions (July 25). US Attorney General William Barr ordered the Federal Bureau of Prisons on Thursday to resume capital punishment for federal prisoners for the first time in nearly two decades, and to change the drugs it uses to carry out executions. Five people, all of whom have been convicted of murder and other crimes, now have executions scheduled for December 2019 and January 2020. There are currently 62 individuals on federal death row, and the federal government has executed only three people since 1988. “The Justice Department upholds the rule of law — and we owe it to the victims and their families to carry forward the sentence imposed by our justice system,” Barr said in a statement. The five inmates to be executed are Daniel Lewis Lee, who murdered a family of three; Lezmond Mitchell, who killed a 63-year-old woman and her 9-year-old granddaughter; Wesley Ira Purkey, who raped and killed a 16-year-old, in addition to two other victims; Alfred Bourgeois, who molested and killed his 2-year-old daughter; and Dustin Lee Honken, who fatally shot five people. The death penalty has been on the decline in America: Although it’s still legal in 29 states, the number of executions carried out each year is falling, and the number of new death sentences is also on the decline. But at the federal level, the Trump administration wants to reverse the trend.

The federal government, the DOJ said, will adopt a new lethal injection protocol that replaces a long-used, three-drug cocktail that was upheld by the Supreme Court in a 2008 case, Base v. Rees, but is now difficult to source. The combination of drugs was used in the majority of executions in the United States until a series of events in 2009 and 2010 made it increasingly rare. Domestic and international pharmaceutical suppliers stopped providing sodium thiopental, the anesthetic used as the first step in the three-drug cocktail. A 2012 court injunction also forced the Food and Drug Administration to block importation of the drug from abroad because it was being used for unapproved purposes. The sodium thiopental shortage forced some states to drop the three-drug cocktail altogether in favor of other drugs. Some temporarily halted executions all together. Others replaced thiopental as the first drug in the cocktail with another controversial sedative, midazolam, which has also come under intense scrutiny and legal challenges because of botched executions in Ohio, Arizona, and Oklahoma.

Instead of the three-drug protocol, the federal government plans to use pentobarbital, a barbiturate used often in veterinary medicine and physician-assisted suicides. Since 2010, 14 states have used pentobarbital in more than 200 executions, according to the DOJ. But just how states obtain the drug has been criticized repeatedly and shrouded in secrecy. Texas, Missouri, and Georgia turned to compounding pharmacies—unregulated by the FDA and shielded from public identification—because licensed manufacturers stopped supplying pentobarbital for executions. The manufacturer of pentobarbital even requires its distributors to sign agreements that they won’t give the drugs to states that perform executions.

The DOJ says its protocol will “closely mirror” one currently in use in Texas, Missouri, and Georgia. Texas currently has 27 doses of pentobarbital in stock, more than enough for its scheduled executions. But Texas had done a better than other states at maintaining stock, and that’s only because it’s repeatedly extended expiration dates past the suggested shelf life. That’s on top of criticisms that compounded pentobarbital already degrades more rapidly. Experts say that could reduce the drug’s potency, making death more painful, and attorneys claim two executions in 2018 were botched because of aged drugs. (The DOJ has not responded to questions about how it will obtain the pentobarbital it plans to use.)

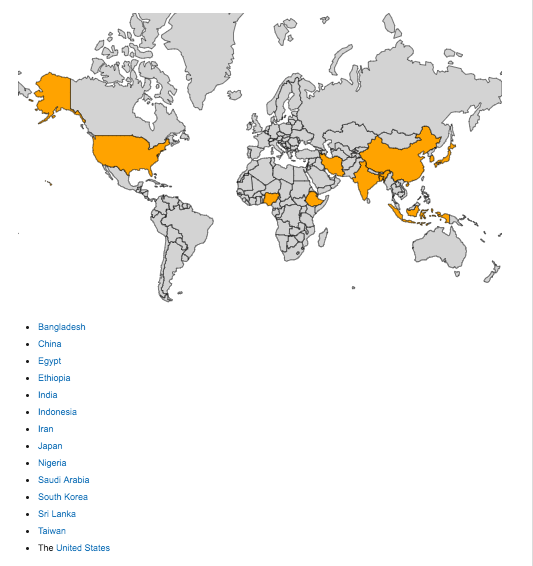

Worldwide

Countries with the Death Penalty

Con — Racism

You have the right to a fair trial by a jury of your peers, but researchers argue your “peers” typically end up being mostly white.

- Researchers find juries in death penalty trials mostly white

- Legal expert: African American disproportionately excluded

- She argues potential solution is to have two separate juries

Alisa Smith, Chair of the Department of Legal Studies at UCF, told Spectrum News that findings from the University of California in recent decades show African Americans are more likely to be disproportionately excluded from death penalty trials. “You can’t exclude a juror based upon race, but you can exclude a juror based upon a belief or a perception that they can’t be fair and impartial,” Smith explained. The findings show that as African Americans become more anti-death penalty, the likelihood of them being excluded in these trials as a juror increase. The research is reflected in the triple-murder trial of Central Florida man Grant Amato, who is accused of killing his parents and brother. Ten people out of the 12 person jury are white, and the alternates are three white men. The point of death qualification is to identify jurors who can be fair and impartial in deciding the ultimate punishment.

Mona Lynch. Death Qualification in Black and White: Racialized Decision-Making and Death Qualified Jurors (2018). Death qualification has been shown to have a number of biasing effects that appear to undermine a capital defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to a fair jury. Attitudes toward the death penalty have shifted modestly but consistently over the last several decades in ways that may have changed the overall impact of death qualification. Specifically, the very large gap between black and white Americans’ current support for capital punishment raises the question of whether death qualification procedures disproportionately exclude African Americans from capital jury participation. In order to examine this possibility, we conducted two countywide death penalty attitude surveys in the California county that has the highest percentage of African American residents in the state. Results show that death qualification continues to have a number of serious biasing effects—including disproportionately excluding death penalty opponents—which result in the significant underrepresentation of African Americans. This creates a death‐qualified jury pool with the potential to be significantly more likely to ignore and even misuse mitigating factors and to rely more heavily on aggravating factors in their death penalty decision making. The implications of these findings for the fair administration of capital punishment are discussed.

Chris Hammer, July 21, 2019, Tracing the Racist History of the Death Penalty in Georgia

Of the nearly 1,500 executions in the United States since 1976, over 70 percent have occurred in the 11 southern states of the former Confederacy. Sociologist R. J. Maratea posits a direct line of racialist social control in these states extending from slavery to the modern criminal justice system.

Maratea focuses on the case of Warren McCleskey, who was executed by Georgia in 1991 for killing a white police officer during an armed robbery. McCleskey’s crime “hit squarely in the face of expected racial etiquette in the Deep South and singled out Warren McCleskey as a black man in need of killing.”

Con — Class/Race

In a brief filed in the case of two death row prisoners, Krasner argued that the “arbitrary manner” in which the death penalty has been applied in Pennsylvania — unfairly targeting people of color and people who are poor — “violates our state Constitution’s prohibition against cruel punishments.” Of the 45 people currently on death row for killing in Philadelphia, 37 are black and four are from other “minority groups,” Krasner’s brief says, adding: “Less than 45% of Philadelphia’s population is black.” “It really is not about the worst offenders,” the district attorney told criminal justice publication The Appeal. “It really is about poverty. It really is about race.”

Con — Errors/Costs

Anthony Graves, July 20, 2019, It’s Time for a Moratorium on the Death Penalty.

You’d think Harris County and the state of Texas would know better. As of today, 13 men have walked free from Texas death row because they were wrongfully convicted. Anthony Graves, one of the authors of this piece, is one of them. He spent more than 18 years behind bars for a crime he did not commit. Twice he faced execution dates.

Besides the unthinkable gravity of such mistakes, the facts show that the death penalty is an extremely expensive way to seek justice. A death penalty trial, including mandatory appeals, is now estimated to cost more than $2 million. We are spending an awful lot of money on a system that has proven to be wrong a bunch of times.

Con — General

Michael Coard, July 21, 2019. Four Facts Why the Death Penalty is Wrong

Scientists agree, by an overwhelming majority, that the death penalty has no deterrent effect. They felt the same way over ten years ago, and nothing has changed since then. States without the death penalty continue to have significantly lower murder rates than those that retain capital punishment. And the few recent studies purporting to prove a deterrent effect, though getting heavy play in the media, have failed to impress the larger scientific community, which has exposed them as flawed and inconsistent.

The latest issue of the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology contains a study by a Sociology professor and a graduate student at the University of Colorado-Boulder (Michael Radelet and Traci Lacock), examining the opinions of leading criminology experts on the deterrence effects of the death penalty.

There is still no evidence that executions deter criminals (2014) By contrast, the question of whether executions discourage criminals from violent acts is not up to the conscience to decide. Despite extensive research on the question, criminologists have been unable to assemble a strong case that capital punishment deters crime “We’re very hard pressed to find really strong evidence of deterrence,” said Columbia Law School’s Jeffrey Fagan. States have been executing fewer and fewer people over the past 15 years. Several states have recently abolished capital punishment, and Gov. Jay Inslee (D) placed a moratoriumon executions in the state of Washington in February. The execution in Oklahoma points to the problems that states that continue the practice are encountering. Meanwhile, however, rates of violent crime are still falling steadily.

John Donahue. There is No Evidence the Death Penalty is a Deterrent Against Crime (2015). So what is the evidence on deterrence? Here the answer is clear: there is not the slightest credible statistical evidence that capital punishment reduces the rate of homicide. Whether one compares the similar movements of homicide in Canada and the US when only the latter restored the death penalty, or in American states that have abolished it versus those that retain it, or in Hong Kong and Singapore (the first abolishing the death penalty in the mid-1990s and the second greatly increasing its usage at the same), there is no detectable effect of capital punishment on crime. The best econometric studies reach the same conclusion.

A number of studies – all of which, unfortunately, are only available via subscripton – purported to find deterrent effects but all of these studies collapse after errors in coding, measuring statistical significance, or in establishing causal relationships are corrected. A panel of the National Academy of Sciences addressed the deterrence question directly in 2012 and unanimously concluded that there was no credible evidence that the death penalty deters homicides.

National Academy of Sciences (2012). Deterrence and the Death Penalty. A panel of the National Academy of Sciences addressed the deterrence question directly in 2012 and unanimously concluded that there was no credible evidence that the death penalty deters homicides.

Arguments in Favor of Capital Punishment (2015)

Pro — Deterrence

David Maulhausen. The Death Penalty Deters and Saves Lives. (2007) .

Federal, state, and local officials need to recognize that the death penalty saves lives. How capital punishment affects murder rates can be explained through general deterrence theory, which supposes that increasing the risk of apprehension and punishment for crime deters individuals from committing crime. Nobel laureate Gary S. Becker’s seminal 1968 study of the economics of crime assumed that individuals respond to the costs and benefits of committing crime.[10]

Pro — Retribution

Russel Christopher, Death Delayed is Retribution Denied (2014).

Gerald Bradley Retribution: The Central aim of Punishment (2003). Only retribution, a concept consistently misunderstood or entirely forgotten during the time I practiced criminal law, justifies punishing criminals. My aim in this paper is to present retribution as the morally justifying aim of punishment.

Pro — Answers to: An Innocent Could be Executed

Capital Punishment and the Conservative Dilemma. (2019). The common argument that a humane society cannot risk even one execution of an innocent is misguided: Just as most of us risk death daily in order to drive automobiles, participate in extreme sports, or watch the Lifetime channel, it is axiomatic that virtually anyone would be willing to bear the infinitesimal risk of wrongful execution in order to obtain the far more important reductions in serious crime that an effective system of capital punishment makes possible. Capital punishment is an extremely difficult business. The alternative is worse.

Alternative Ways to Conduct the Death Penalty

Life in Prison, or the Death Penalty? (2019) If we are to have such a penalty, we should implement it in a way that forces more contemplation of the penalty by the citizens implicated in it. Conducting executions publicly would be one especially grotesque way—but it would also be imperfect, since anyone could just look away, and in any case, a public spectacle would further degrade the dignity of the victim and the proceedings. In classical Islamic law, executions and other punishments are required to be public, and in France, public executions continued until the Second World War.

Instead, I suggest, if we are to kill criminals, that the execution be conducted not by professionals, but by a randomly selected adult citizen. The model would be jury duty or conscription. If your number is called, you must report to the penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana, and be ready at an appointed time to read the sentence aloud to the criminal and press a button that sends pentobarbital into his veins. The duty would end once the selected citizen failed to find a pulse.

Websites — Con

ACLU

Amnesty International

California Innocence Project

Equal Justice Initiative

Next to Die

More Citations