Introduction: What is Ranked Choice Voting?

Ranked-choice voting (RCV) is a type of voting system where voters are given the option to rank their preferred candidates in order of preference.

Here’s an example to help you understand how it works:

Let’s say there are three candidates running for class president: Jane, John, and Sarah. In a ranked-choice voting system, instead of just choosing one candidate, voters would rank all three candidates in order of preference.

So, a voter might choose to rank Jane as their first choice, John as their second choice, and Sarah as their third choice. Another voter might choose to rank John as their first choice, Sarah as their second choice, and Jane as their third choice.

Once all the votes are cast, the counting process begins. First, all of the first-choice votes are counted. If any candidate receives more than 50% of the first-choice votes, they are declared the winner.

However, if no candidate receives more than 50% of the first-choice votes, then the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. The votes for the eliminated candidate are then redistributed to the remaining candidates based on the voters’ second-choice preferences.

This process continues until one candidate receives more than 50% of the votes and is declared the winner.

Where has this been tried in the US?

“A growing number of U.S. elections are being conducted with RCV. Over 20 U.S. cities1 now use RCV in single-winner contests, with nearly as many recently adopting rules to soon implement RCV. State legislatures in Utah and Virginia have expanded options for using RCV at the local level, and several states used RCV for their 2020 Democratic presidential primaries: (Donovan 2022). Two states use or will be using RCV for statewide and federal elections: Maine since 2018 (Santucci 2018) and Alaska starting in 2022

Recently, New York City adopted RCV for its mayoral election and Alaska adopted it for its state and federal elections [Bussuiret & Palto, 2023]

Maine. In 2018, Maine became the first state in the U.S. to use ranked choice voting in statewide elections for federal elections (the U.S. Senate, U.S. House of Representatives), and Governor. [MIT Lab — This article describes that and argues that it did not accomplish the goals its proponents set out to accomplish]

New York City. In 2021, New York City used ranked choice voting for its mayoral race as well as for other citywide offices such as comptroller and public advocate. [The City]

San Francisco. San Francisco has used ranked choice voting since 2004 for local elections, including those for mayor, city attorney, and members of the Board of Supervisors. (National Civic League — Note: This article does support RCV, arguing it has increased voter engagement).

Minneapolis. Minneapolis has used ranked choice voting since 2009 for local elections, including mayor and city council. In 2009, Minneapolis became one of the largest cities to utilize ranked choice voting (RCV) rules for municipal elections. St. Paul followed suit for mayoral and city council elections beginning in 2011. Considering the overwhelmingly positive effects of the rule change, the Twin Cities—with the recent additions of St. Louis Park, Minnetonka, and Bloomington—are likely to rely on RCV for the foreseeable future. [Zach Spindler-Krage — This article discusses its use in the Twin Cities and supports it] [Note: It has not been tried state-wide (Calligan, and Calligan discusses some of the problems with making it a state-wide vote]

Oakland. Oakland, CA has used ranked choice voting since 2010 for local elections, including those for mayor and city council. [Fermoso, 2022]

You should be prepared to debate the pros and cons of how it worked in each of these cities.

Other cities and states that have used or are considering the use of ranked choice voting include Santa Fe, New Mexico (Fair Vote) and Alaska (AP).

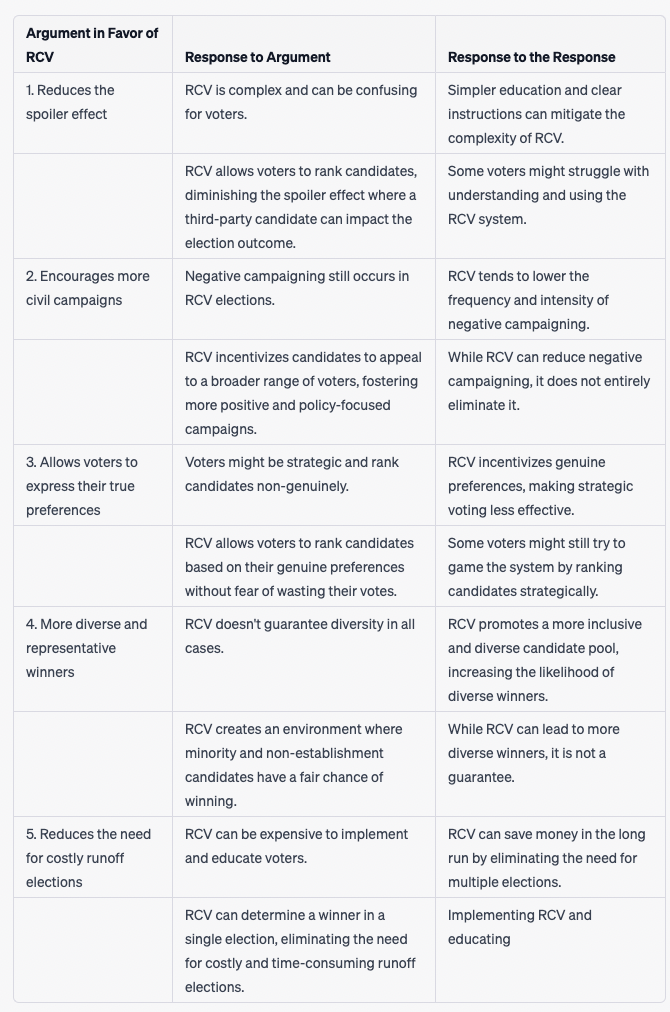

Pro Arguments with Con Responses

Promotes majority support. With ranked choice voting, the winning candidate must receive a majority of votes, meaning more than 50%. This ensures that the winning candidate has broad support from voters and can help reduce the likelihood of candidates winning with a small percentage of the vote. (Ballotpedia)

RCV allows voters to rank candidates in order of preference, reducing the risk of vote splitting and spoiler candidates, which can undermine the legitimacy of election outcomes (Guiterrez, 2021; Maskin 2022)). RCV enables voters to provide a more complete report of their candidate preferences on the ballot, allowing for a more accurate reflection of the electorate’s will (Holden, 2022). RCV combines the primary and general elections into one, reducing the need for costly and time-consuming runoff elections, which can have lower voter turnout and potentially less representative outcomes.

Numerous studies and real-world examples have demonstrated the positive effects of RCV on electoral legitimacy and representation (More Choice San Diego; Richie, 2017; Chadha, 2021).

Response: While promoting majority support is a key benefit of ranked choice voting, some critics argue that it can actually lead to less democratic outcomes. Specifically, they argue that if a candidate with a large lead in first-choice votes is eliminated and their voters’ second-choice candidates are not favored by the remaining voters, the winning candidate may not be the most popular candidate overall. This could result in a candidate winning with less overall support than their opponents. Further, RCV has been fiercely opposed by Maine’s Republican Party, especially after a loss in a 2018 congressional election by a Republican to a Democrat in a “come-from-behind victory.” (In a “come-from-behind” victory under RCV, the winner of the first-preference votes loses after the allocation of additional-preference votes.) In a survey experiment administered on 3,471 registered voters throughout the U.S., voters were less satisfied with RCV than with runoff or plurality, and especially less satisfied with a come-from-behind victory (Cerrone, 2021). Although supporters claim that IRV is superior to the traditional primary-runoff election system, research on Instant Runoff Voting (IRV) [IRV is another name for Ranked Choice Voting] is limited. We analyze data taken from images of more than 600,000 ballots cast by voters in four recent local elections. We document a problem known as ballot “exhaustion,” which results in a substantial number of votes being discarded in each election. As a result of ballot exhaustion, the winner in all four of our cases receives less than a majority of the total votes cast, a finding that raises serious concerns about IRV and challenges a key argument made by the system’s proponents (Burnett, 2015).

Encourages positive campaigning. Since candidates in ranked choice voting systems are encouraged to appeal to a broad range of voters, they tend to focus on issues and policies that are important to voters rather than engage in negative campaigning against their opponents. (Donovan, 2016; Fair Vote 2015; Drutman 2020).

Response: While ranked-choice voting may discourage negative campaigning, some critics argue that it can also lead to more strategic campaigning. Specifically, candidates may choose to only focus on issues that are likely to appeal to their base and avoid taking positions that may be more polarizing (Buisseret, 2023). This could result in a more limited discussion of the issues and less emphasis on finding common ground.

Strategic vote-seeking can be polarizing because it encourages candidates and political parties to adopt extreme positions to appeal to their base rather than converging towards the median voter. This can lead to increased polarization among the electorate, as supporters of non-viable parties may cast strategic votes based on their preferences for viable parties.

In turn, this can create a feedback loop where politicians adopt more polarized positions to secure strategic votes, further driving polarization. Additionally, strategic voting can contribute to the perception of increased polarization, which may lead politicians to vote on policies based on false perceptions or strategic considerations. This can result in a decline in representative democracy, as voters may be more willing to accept undemocratic strategic voting or polarized policies from their leaders if they believe it will help them achieve their desired outcomes. Overall, strategic vote-seeking can exacerbate political polarization by encouraging extreme positions and altering the behavior of both politicians and voters.

Polarization has several negative effects on democracy.

It rewards extreme positions and weakens centrist moderates. Polarization encourages politicians to adopt extreme positions to appeal to their base, sidelining moderate voices and reducing the chances of compromise and cooperation.

It affects individual perceptions and is hard to reverse. Polarization can lead to a political environment filled with vitriol and mutual distrust, making it difficult to reverse once in place. This can result in an ineffective democracy as policy-making is impacted by polarization. (Eager, 2021)

Policy gridlock. As opposing sides become more polarized, they are less likely to cooperate on policy-making, leading to gridlock and an inability to address pressing issues.

Democratic erosion. Polarization can contribute to democratic backsliding, as the public’s faith in government institutions dwindles. This can lead to a domino effect, where the public perceives Congress to be less successful, further eroding faith in democracy.

Threat perception. Polarization can cause supporters of opposing parties to view each other as threats to the nation’s well-being, further exacerbating divisions and undermining democratic norms.

Tyranny of minorities. Pernicious polarization can stem from the influence of minority factions within political parties, leading to disproportionate representation and undermining the democratic principle of majority rule.

Overall, polarization harms democracy by fostering extreme positions, eroding public trust, creating policy gridlock, and undermining democratic norms and principles.

Response: RCV promotes collaboration and civility among competing candidates, as they may seek to become the second or third choice of voters who support other candidates (John, 2011). This can lead to more deliberative campaigns and a focus on policy issues, potentially reducing the polarization often associated with the two-party system.

Saves money. Ranked-choice voting can save money by eliminating the need for primary and runoff elections. With ranked choice voting, a single election can determine the winner, which can reduce the cost of elections for taxpayers.

Response: While ranked choice voting can save money by eliminating the need for primary and runoff elections, some critics argue that it can also increase the cost of administering elections. Specifically, implementing and educating voters about a new voting system can be expensive and time-consuming. Additionally, the need for more complex vote-counting procedures can add to the cost of the election. In New York, the election dragged on for many weeks (King & Montellero, 2021), thought the was at least partly due to a specific mistake officials made.

Increases voter turnout/Engagement. Ranked choice voting can increase voter turnout by giving voters more choices and a greater sense of control over the outcome of the election. This can be particularly appealing to young voters who may feel marginalized in a traditional two-party system (Juliech, 2021).

Ranked-choice voting (RCV) has been shown to positively affect voter turnout. By allowing voters to support their ideal candidate without feeling like their vote would be wasted, RCV incentivizes participation in the election process. In the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, RCV led to a 9.6-point increase in turnout, with a higher effect on turnout in precincts with higher prevalence rates. RCV also increased turnout among African Americans, Latinos, and Asians more than the general electorate, as having more candidates on the ballot who resonate with voters of color gives them more reason to vote.

In New York City’s 2021 primary, an analysis by Citizens Union found that RCV had more benefits than drawbacks, increasing voter interest and participation, reducing wasted votes, eliminating costly runoffs, and leading to a more diverse pool of candidates. Turnout increased in 41 of the 44 races contested in both the 2013 and 2021 primaries. Overall, RCV has been found to boost voter turnout and encourage a more engaged electorate. (AM New York) In the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, RCV led to a 9.6-point increase in turnout, with a higher effect on turnout in precincts with higher poverty rates.

Response: Ranked choice voting (RCV) is a voting system used commonly around the world, but only rarely in the United States. I present here a study that investigates how American voters act in an RCV election. Using a survey experiment design, I compare the election outcome and the behaviors and attitudes of voters in a plurality election to an RCV election. I find evidence suggesting RCV may not significantly change election outcomes and have no positive impact on voters’ confidence in elections and the democratic process. Study participants who voted in the RCV treatment were not any more likely to prefer RCV elections to plurality or majoritarian elections, and, overall, most voters do not prefer to vote in RCV elections and do not think that they result in fair election outcomes (Nielson, 2017), (Kimball): We find that RCV helps reduce the substantial drop in turnout that commonly occurs between primary and runoff elections. Otherwise, reducing the RCV does not appear to have a strong impact on voter turnout and ballot completion.

Promotes candidate diversity. RCV has also increased the number of women and people of color running for office, resulting in a more diverse pool of candidates and a more representative electorate (Scott & Santucci, 2021). In the 2021 New York primary, RCV was found to increase voter interest and participation, reduce wasted votes, eliminate costly runoffs, and lead to a more diverse pool of candidates.

Support from racial minorities. We find that a short explanation of the vote transfer properties of RCV does not increase public support for the voting rule. Furthermore, when given a choice between the single and ranked voting methods, a large majority among four racial groups prefers the status quo option of the single vote. However, Latino, Black, and Asian American respondents evaluate ranked choice voting more positively and express a stronger preference for RCV than White respondents. Furthermore, communicating that RCV helps elect more women and people of color increases preferences for RCV among Latino, Black, and Asian American voters, but not among White voters (Scott, 2021).

Response: Kimball & Donovan (2016): In a case study of Minneapolis, we find similar levels of socioeconomic and racial disparities in voter participation in plurality and RCV elections.

Response: After estimating the level of racially polarized voting with rank clustering and ecological inference models, we show that switching from FPTP to RCV did not alter the level of racially polarized voting for the overall electorate and all pairs of racial and ethnic groups we study (Landsman, 2022).

Reduces the spoiler effect. Ranked choice voting can help reduce the spoiler effect, where a third-party candidate takes votes away from a major party candidate and potentially swings the election in favor of the other major party candidate. With ranked choice voting, voters can rank their preferred third-party candidate first without worrying that they are “wasting” their vote, as their vote will be transferred to their next preferred candidate if their first choice is eliminated.

Response: While ranked choice voting can help reduce the spoiler effect, some critics argue that it may also lead to a lack of choice for voters. Specifically, if third-party candidates are not able to gain enough support to advance in the voting process, voters may be forced to choose between the two major-party candidates, which could limit the diversity of ideas and candidates in the political process.

Promotes independent candidates. RCV reduces the spoiler effect, allowing voters to support third-party or independent candidates without fearing that their vote will be wasted or inadvertently help elect their least preferred candidate. This can lead to a more diverse range of candidates and potentially weaken the dominance of the two major parties (Simons 2022)

Response: In 2019 two cities in Utah began using a type of ranked-choice voting for elections. And while ranked-choice voting is more effective in increasing minority representation than first past the post voting, Utah’s version may be harmful to minorities, argue Jack Santucci and Benjamin Reilly. As votes under this system can ‘cascade’ downwards from the first winner to others from the same party or group, they write that ‘block-preferential’ voting could lead to unfair outcomes if adopted more widely ( Reilly).

Con and Pro Responses

Majoritarian failures. From the perspective of social choice theory, ranked-choice voting (RCV) is known to have many flaws. RCV can fail to elect a Condorcet winner and is susceptible to monotonicity paradoxes and the spoiler effect, for example. We use a database of 182 American ranked-choice elections for political office from the years 2004-2022 to investigate empirically how frequently RCV’s deficiencies manifest in practice. Our general finding is that RCV’s weaknesses are rarely observed in real-world elections, with the exception that ballot exhaustion frequently causes majoritarian failures. (Squire, 2023).

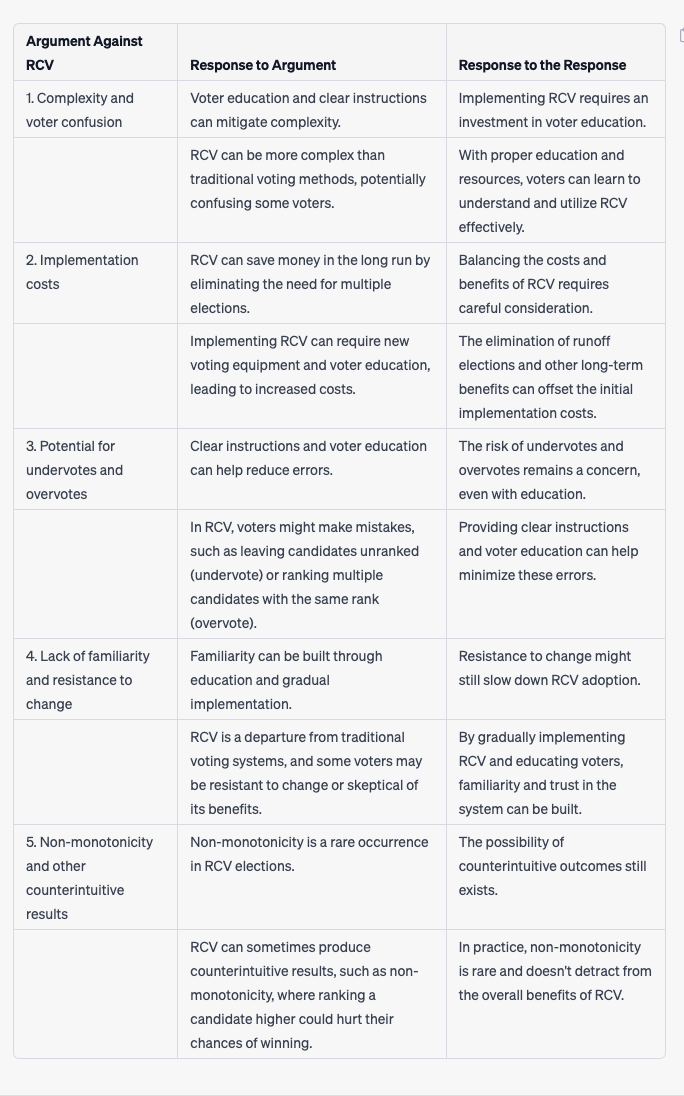

Time consuming. While ranked choice voting may increase voter turnout, some critics argue that it may also lead to confusion among voters. Specifically, voters may not fully understand how to rank their choices, which could result in spoiled ballots or a lower voter turnout. Additionally, some critics argue that ranked-choice voting can be more time-consuming for voters, which could discourage some from participating.

Complexity. Critics argue that RCV can be too complicated for the average voter to understand, potentially leading to confusion and errors in casting ballots. There is some research that suggests that ranked-choice voting can be more complicated for voters. For example, a report by the Alaska Policy Forum states that ranked-choice voting entails a much more complicated decision, and to fully participate, voters must rank-order all of the candidates (Townsend, 2020). There is some evidence that ranked-choice voting can be confusing for voters. (A)policy analysis found that ranked ballots are three to four times more likely to be spoiled than traditional ballots (NPR). However, I couldn’t find any specific evidence that ranked-choice voting confused voters in the New York City Mayoral election. Would you like me to look up more information on this topic?

Response: Studies have shown that voters tend to have high levels of understanding and satisfaction with RCV systems (Donovan, 2022).

Implementation Challenges. Implementation challenges: Implementing RCV may require changes to voting equipment, voter education, and election administration, which can be costly and time-consuming (Vasilogambros, 2022). A lack of support by those administering the program may also make it hard to implement (Anthony 2021).

Response: Proponents argue that the long-term benefits of RCV, such as eliminating costly runoff elections and promoting more representative outcomes, outweigh the initial implementation costs. Rhode (2020) argues that any cost increase is not meaningful.

Polarization. Critics argue that RCV may inadvertently reward extremist candidates in polarized electorates, as moderate candidates may be eliminated early in the counting process (McDaniel 2018). This argument is covered in more detail above.

Voter Fatigue. Ranking multiple candidates may lead to voter fatigue, causing them to not fully utilize the ranked preferences on the ballot (Kimball, 2016)

Response: However, research has shown that RCV increases voter turnout and engagement, suggesting that the benefits of RCV outweigh potential fatigue.. RCV’s utility as a solution to inter-party coordination problems helps to explain its appeal in both countries, underscoring the potential benefits of a comparative analytical approach. This article examines this history of adoption and then turns to a comparison of recent RCV elections in Maine with state elections in New South Wales and Queensland, the two Australian states that share the same form of RCV as that used in the United States. This comparison shows how candidate and party endorsements influence voters’ rankings and can, over time, promote reciprocal exchanges between parties and broader systemic support for RCV. Such cross-partisan support helps explain the stability of RCV in Australia, with implications for the system’s prospects in the United States. (Reilly, 2021)

Perceived partisanship. Some critics argue that RCV is promoted by certain political groups to gain an advantage, casting doubt on its neutrality.

Response: However, RCV does not structurally favor any particular party and is intended to improve the overall electoral process (Cervas, 2021).

Unconstitutional. This Comment argues that, although unanimous, the decisions upholding RCV under the Federal Constitution are incorrect. These opinions are cursory and rest on incorrect premises about how RCV elections operate in practice and the true burdens that RCV systems impose on voting rights. First, Part I describes the logistics of RCV, the legal standard for evaluating election laws, and specific legal challenges to RCV. Part II details how RCV burdens voting rights and how courts have relied on incorrect grounds to uphold RCV systems. Ultimately, this Comment argues that going forward, once the faulty premises are corrected and the proper legal standard is applied, courts should hold that RCV violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (Bryer, 2021).

Additional Bibliography

General

Ranked Choice Voting Gains Momentum (2021)

Variants of Ranked-Choice Voting from a Strategic Perspective (2021). Abstract: Ranked-choice voting has come to mean a range of electoral systems. Broadly, they can facilitate (a) majority winners in single-seat districts, (b) majority rule with minority representation in multi-seat districts, or (c) majority sweeps in multi-seat districts. Further, such systems can combine with rules to encourage/discourage slate voting. This article describes five major versions used, abandoned, and/or proposed for US public elections: alternative vote, single transferable vote, block-preferential voting, the bottoms-up system, and alternative vote with numbered posts. It then considers each from the perspective of a ‘political strategist.’ Simple models of voting (one with two parties, another with three) draw attention to real-world strategic issues: effects on minority representation, importance of party cues, and reasons for the political strategist to care about how voters rank choices. Unsurprisingly, different rules produce different outcomes with the same sets of ballots. Specific problems from the strategist’s perspective are: ‘majority reversal,’ serving ‘two masters,’ and undisciplined third-party voters (or ‘pure’ independents). Some of these stem from well-known phenomena, e.g., ranking truncation and ‘vote leakage.’ The article also alludes to ‘vote-management’ tactics, i.e., rationing nominations and ensuring even distributions of first-choice votes. Illustrative examples come from American history and comparative politics. A running theme is the two-pronged failure of the Progressive Era reform wave: with respect to minority representation, then ranked voting’s durability.

Editor’s Introduction: The Promise and Peril of Ranked Choice Voting (2021). Dissatisfaction with two-party politics is at an all-time high in the US. As extreme polarization and minority rule persist, a possibility of an electoral reform becomes increasingly more likely. This editor’s introduction discusses the ranked choice voting (RCV) as an alternative to the current single-member geographic districts with winner-take-all plurality elections in the US. The articles for this thematic issue critically evaluate whether RCV lives up to its promise in improving democracy in the US. Like any rule or institutional change, it has benefits and drawbacks. The empirical and historical research presented here focuses on the implementation and use of RCV in the US compared to other countries. This thematic issue offers new insights into the promise and perils of RCV as a way to aggregate votes in elections that ensure that the winning candidate receives a majority of the votes cast.

Election Reform and Women’s Representation: Ranked Choice Voting in the U.S. (2021). Ranked choice voting first gained a foothold in the U.S. during the Progressive Movement in the 20th century as calls for electoral reforms grew. Ranked choice voting was implemented in many cities across the U.S. in both single- and multi-seat districts. But, by the 1940s it became a victim of its own success, turning the tides of the hegemonic white male leadership in U.S. legislative bodies with the election of women. Since the 1990s, ranked choice voting has once again gained traction in the U.S., this time with the focus on implementing single seat ranked choice voting. This article will build on the existing literature by filling in the gaps on how ranked choice voting—in both forms—has impacted women’s representation both historically and in currently elected bodies in the U.S.

Politics Transformed? How Ranked Choice Voting Shapes Electoral Strategies (2021) We compare electoral outcomes under plurality rule versus ranked choice voting (RCV). Candidates compete by choosing platforms that can either mobilize their core supporters, or instead attract undecided voters. RCV exacerbates platform polarization in contexts of low voter engagement, strong partisan attachments, and imbalances in the candidates’ share of core supporters. RCV may increase or decrease voter turnout relative to plurality rule, and strong partisan attachments increase the likelihood that the winning candidate receives a minority of votes cast.

Pro

An Introduction to Ranked Choice Voting

The Conservative Case for Ranked Choice Voting (2021)

Drutman, Lee. 2020. Breaking the two-party doom loop: The case for multiparty democracy in America. Oxford University Press. Drutman argues RCV forces candidates to appeal to a larger base.

Donovan et all (2016). Campaign civility under preferential and plurality voting

An Assessment of Ranked-Choice Voting in the San Francisco 2004 Election

Ranked-choice voting and the spoiler effect (2023). In the popular debate over the use of ranked-choice voting, it is often claimed that ranked-choice voting is less susceptible to the spoiler effect than the plurality method. We choose a definition of the term “spoiler effect” based on a survey of the popular discourse surrounding ranked-choice elections and examine whether ranked-choice voting outperforms plurality with respect to this definition. We provide analytical results under the impartial anonymous culture and impartial culture models, and simulation results using four models of voter behavior, two random and two single-peaked. We also give empirical results using a large database of American ranked-choice elections. All of our results suggest that ranked-choice voting is superior to plurality with respect to the spoiler effect.

Upending Minority Rule: The Case for Ranked-Choice Voting in West Virginia (2019-2020).

Ranked Choice Voting in Mayoral Elections (2022). Numerous cities across the U.S. have recently switched to ranked choice voting in their local mayoral elections. Proponents argue that, by allowing voters to fully express their preferences over the candidates, voter satisfaction and, ultimately, turnout will improve. Opponents are concerned over the number of candidates who enter the race, as it increases the chances of someone only supported by a minority taking office. To date, there has not been an empirical analysis of ranked choice voting’s effects. First, using the Synthetic Control Method on three large U.S. cities who switched relatively recently, I explore the voting rule’s causal impact. I show that the voting rule does not lead to a noticeable change in voter turnout, but does dramatically increase the number of candidates who compete. Second, I explore the public finance consequences comparing budgets of both these three cities to their synthetics and exploiting a panel data set of municipal budgets, which allows me to include additional treated cities. I provide evidence that budget deficits grow after its implementation. Evidence indicates that the increased spending occurs in public welfare programs.

Con

Where’s the Evidence Supporting Ranked-Choice Proponent’s Claims? (April 2023). This article refutes the common arguments in favor of RCV (voter engagement, minority representation, etc)

Rank Deficiency? Analyzing the Costs and Benefits of Single-Winner Ranked-Choice Voting (2020). In the past decade, debate around the effects of the instant runoff voting (IRV) has intensified, as proponents seek to build upon a victory in Maine to expand its use to more states. However, there has relied on unsubstantiated claims from both sides, as it has only been used in a single statewide election. This lack of information around IRV is compounded by the fact that relatively little work has been done around the behavioral impacts of IRV in a multi- party setting, with most of the elections happening in cities that lean strongly Democrat. This study seeks to better understand this reform by being the first to holistically analyze both the micro-level and macro-level impacts of IRV. In doing so, I find strong experimental and observational evidence to suggest that the negative impacts of IRV outweigh any positive effects, and that elite-led opinion may serve as a mitigating factor.

Ranked Choice is a Bad Choice (2021). This outlines a basic, organized case against RCV.

Ranked Choice Voting: A Disaster in Disguise (2022). This is a thorough attack on RCV.

Freedom Foundation of Minnesota (2021) Ranked choice voting: A risk voters shouldn’t take,” Freedom Foundation of Minnesota. This is a podcast That is useful to listen to if you want to understand the basic arguments about RCV.

Alaska Policy Forum (2020). The failed experiment of ranked-choice voting: A case study of Maine and analysis of 96 other jurisdictions,” This is a comprehensive attack on RCV.

Isabelle Christie (2020). Expert report reveals weaknesses of RCV.Maine Wire. This article quotes a Princeton professor who wrote a legal brief against RCV.

Jason McDaniel (2016). Ranked choice voting likely means lower turnout, more errors,” Cato Unbound. This article argues that we should decide if an election system is good based on the ease of participation (a good Con framework argument and that RCV makes participation more difficult.

Stephen H. Unger (2013). Instant run-off voting: Looks good—But look again,” Columbia University Blogs (2013),

David Sharp (2016) Ranked choice as easy as 1, 2, 3? Not so fast, critics say

Sean Fisher, Amber Lee, and Yptach Lelkes. 2021. Electoral Systems and Political Attitudes: Experimental Evidence— RCV increase animosity in campaigns.

Joseph Cerrone and Cynthia McClintock. 2021. “Ranked-Choice Voting, Runoff, and Democracy: Insights from Maine and Other U.S. States.RCV does not increase minority representation

David C. Kimball and Joseph Anthony. 2016. “Voter Participation with Ranked Choice Voting in the United States,” Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association; Sarah John, Haley Smith, and Elizabeth Zack. 2018. “The alternative vote: Do changes in single-member voting systems affect descriptive representation of women and minorities?” Electoral Studies 54:

90-102. — There are more minority candidates but they do not win

Cynthia Richie Terrell, Courtney Lamendola and Maura Reilly. 2021. “Election Reform and Women’s Representation: Ranked Choice Voting in the U.S.” Politics and Governance 9(2): 332–343. — There were only more candidates in the Bay area because more ran nation-wide

Jason A. McDaniel. 2016. “Writing the Rules to Rank the Candidates: Examining the Impact of Instant-Runoff Voting on Racial Group Turnout in San Francisco Mayoral Elections,” Journal of Urban Affairs 38:387-408. and Francis Neely, Corey Cook, and Lisel Blash. 2006. “An Assessment of Ranked-Choice Voting

in the San Francisco 2005 Election.” Daly City, CA: Public Research Institute, San Francisco State University. — Reduced minority representation

David C. Kimball and Joseph Anthony. 2016. “Voter Participation with Ranked Choice Voting in the United States,” Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association.preferential and plurality voting.” Electoral Studies 42: 157-163. 10 Voter confusion —

artha Kropf. 2021. “Using Campaign Communications to Analyze Civility in Ranked Choice Voting Elections” Politics and Governance 9(2): 280–292. — Negative Twitter campaigning in RCV cities

11 Jesse Clark. 2020. “Rank Deficiency? Analyzing the Costs and Benefits of Single-Winner Ranked-Choice Voting.” Negative campaigning in RCV in Minnesota